(4TH INFANTRY DIVISION) IN THE HURTGEN FOREST,

GERMANY, 16-22 NOVEMBER 1944

(RHINELAND CAMPAIGN)

By Lieutenant Colonel James W. Haley

THE BATTALION ATTACK - 16 NOVEMBER

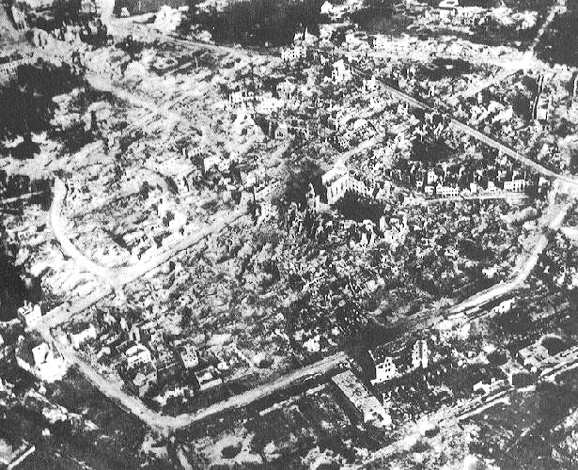

The morning of 16 November dawned cloudy and overcast. After a hot breakfast the troops of the 2nd Battalion occupied themselves with last minute preparations for the attack and with watching the skies, hoping that they would clear. They well knew that the air support would make the advance much easier, and less costly. And their hopes were not in vain. By 1100 the clouds had broken and the sun began to break through. The air effort was ordered and began at 1145 hours in conjunction with a massive artillery preparation. The forest literally reverberated with the noise of the explosions. This air attack was the largest ever made in support of a ground operation, including the "break-out" at St. Lô. Over 3000 bombers of all types from the United States and British Air Forces dropped roughly 10,000 tons of bombs on the enemy positions in and around Düren and the surrounding towns. All of these targets were almost completely destroyed but the enemy positions close in front of the 4th Infantry Division were untouched by the bombs. This was due to the fact that no clearly defined bomb line close in to the front could be defined. However, the enemy's rear areas and lines of communication within the 4th Infantry Division's zone of action were badly disorganized. 32

On 16 November 1944, 97% of Jülich was destroyed during Allied bombing,

since it was considered one of the main obstacles to the occupation of the Rhineland,

although the city fortifications, the bridge head and the citadel had long fallen into disuse.

The results of the artillery preparation were much more evident to the Battalion. The shells could be heard whining overhead and crashing into the trees showering the area with fragments. While the heavy guns continued to work over the rear areas, the light battalion in support of the 8th Infantry shifted to the area close in to the line of departure at H minus fifteen minutes. The forest was literally being chewed to pieces by the exploding shells. Trees were shot off and fell across each other making large areas absolutely impenetrable. However, as it was soon to be evident, the Germans were so well dug in that they suffered only slight casualties.

The distance from the Battalion's assembly area to the line of departure was about 1000 yards. The route forward was along the road running northeast from Bend in order to avoid the rough terrain and conserve the strength of the troops. (See Map D) Even this road was so poor and muddy that the movement was difficult. The Battalion moved out at 1100 in a column of companies with E Company leading, followed.by F Company and then G Company. As the head of the column approached the bottom of the ravine, enemy artillery fire began to fall on the bridge across the stream. It was suspected that this fire was being directed by observers from Hill 280. (See Map D) By increasing the interval between men and double timing, the Battalion succeeded in crossing the bridge, suffering only four casualties. As the Battalion proceeded up the steep slope, the enemy artillery fire continued to fall on the bridge ad began to search the east slope of the ravine. 33

Hill 399, with Wehebach Reservoir in the background.

Hill 280 is in the upper left corner.

As you can see excellent spot for observation.

By 1230 hours E and F Companies were deployed and G Company was in covered positions just east of the road running along the bottom of the ravine. From the Battalion Observation Post, the Battalion Commander could not see his companies but was in contact with then by radio and wire. At 1245 hours E and F Companies crossed the line of departure with two platoons abreast under cover of our artillery fire which was blasting the area just over the top of the slope. Enemy artillery fire continued to fall throughout the area but as yet was not too intense. No small arms fire was being encountered since the area was defiladed.

As the attack reached the top of the slope, the friendly artillery and mortar fire was shifted and immediately the assaulting companies came under heavy machine gun and artillery and mortar fire. The enemy machine guns were so well camouflaged and visibility so limited that they could not be located.

As the advance continued, the enemy artillery and mortar fire began to increase in volume and became very accurate. Tree bursts from the 150 mm artillery pieces and 120 mm mortars began. to take a heavy toll of the assault companies.

The attack was pressed and the advance continued against increasing resistance for about 200 yards. Suddenly, the leading elements broke through the underbrush into a smell clearing along the fire break. About 25 or 30 yards from the edge of the underbrush and along the fire break a barbed wire entanglement of triple concertina higher than a man's head extended across the entire front. (See Map D) The fact that an anti-personnel mine field extended along the near edge of the wire was determined by several men having their feet blown off by the wooden Shü mines. The enemy small arms fire which had been searching for the attacker heretofore now became deadly accurate. The Germans, perfectly concealed themselves, could see every man of E and F Companies who moved into the fire break.

It was at this time that it became evident that the enemy had learned how to mass his artillery. It was later learned that the German commander of the corps holding this area was an artillerymen and there was no doubt but what he knew how to employ his artillery. It also became evident that E and F Companies were caught in an area on which the Germans had previously registered their artillery and mortars. In spite of all efforts the advance was halted and E and F Companies were pinned to the ground by the deadly machine gun fire from the front and flanks. Friendly artillery and mortar fire was brought in as close as possible but still the enemy fire continued. By this time the enemy artillery fire had reached a crescendo. Experienced officers of the Battalion, who had fought all through Normandy and across France, later stated that they had never before seen the Germans mass so much artillery fire on one area. Men trying to dig in were blown to pieces where they lay. If a man rose from the ground he was almost certain to be hit by the machine gun fire even if he escaped the artillery and mortars. The support platoons of both E and F Companies were committed but were stopped as soon as they hit the mine field and barbed wire. Officers and non-commissioned officers, exhibiting the highest order of bravery and leadership, moved along the line encouraging the men and trying to find some way forward until there were but few left who had not been killed or wounded. Still neither company could advance. No bangalore torpedoes or other means of blowing gaps through the mines and wire had been provided since the information available prior to the attack had not revealed the presence of these obstacles. 34

Back at the Battalion Observation Post, which was only about 400 yards in rear of the front lines, the situation was little better. Enemy artillery fire was pounding the entire east slope of the ravine and movement of any kind was very difficult. At 1400 the Battalion Commander talked to the Regimental Commander by telephone and explained that his Battalion was unable to advance and was suffering very heavy losses. He was informed by the Regimental Commander to continue the attack in an effort to break through the enemy resistance. 35

Immediately after talking to the Regimental Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Jackson decided to commit G Company in an envelopment to the left. The Company Commander of G Company, Captain Earl L. Stackhouse, was called to the Battalion Observation Post to receive the order. While Captain Stackhouse was working his way up the slope of the ravine, Captain Hillebrandt of F Company was also working his way back from the front lines to personally report the situation to the Battalion Commander. These two Company Commanders, both seasoned combat leaders, arrived at the Battalion Observation Post simultaneously and before either had talked to the Battalion Commander , both were seriously wounded by an enemy artillery concentration that blasted the area. First Lieutenant George K. Devine, Executive Officer of G- Company, was then called to the Battalion Observation Post to receive the order for the commitment of G Company and First Lieutenant Robert H. Eusted, Executive Officer of F Company took over that company. Command of E Company was assumed by First Lieutenant John E. Middleton, Executive Officer of E Company at about this same time since the Company Commander, First Lieutenant Dooley, had been mortally wounded a few minutes previously. 36

At 1530 hours G Company moved from its reserve position, deployed with two platoons abreast, and started advancing up the hill with its left flank on the road running east from Schevenhütte. When the top of the hill was reached the company came under machine gun and rifle fire and was pounded by the enemy artillery and mortars. The advance continued until the clearing along the fire break was reached and here G Company, as E and F Companies had been, was stopped. Now all three companies were along the same general line and all were being severely mauled. The entire area was literally covered with the dead and wounded of the Battalion as only limited evacuation had been possible due to the heavy enemy fire. 37

About 1700, the Battalion Commander, having exhausted all means to break the enemy line without success, ordered the companies to withdraw to the line of departure and to tie in for the night. By this time the enemy fire had slackened somewhat but many additional casualties were suffered in the withdrawal. The movement was completed by dark and the front had settled down to a relatively quiet situation.

About 1800 the Battalion Commander called the Regimental Commander by telephone from the Observation Post and requested that the Battalion be withdrawn. He explained that the Battalion had suffered heavily, having lost all rifle company commanders and a large proportion of platoon leaders and non-commissioned officers. However, this request was refused and he was ordered to continue the attack at 0900 on the following morning, 17 November. 38

As darkness descended on the forest a tremendous task faced the 2nd Battalion. Plans for the next morning's attack had to be made; orders had to be issued; food, water and ammunition had to be brought forward; and the largest job of' all, the wounded had to be evacuated. Furthermore, the depleted rifle companies had to undertake some kind of reorganization. The night became miserably cold and wet but blanket rolls for the men were out of the question. Everything had to be hand carried up the steep slope of the ravine and too many things took priority over the rolls. The Ammunition and Pioneer Platoon worked unceasingly throughout the night carrying supplies up the hill and bringing casualties down. The night was pitch black and the casualties could only be found by their cries of pain. A round trip for a litter team required from one and one-half to two hours and many of the wounded died from exposure before they could be evacuated. The number of wounded officers and enlisted men who passed through the aid station during the night plus those who had been killed totaled approximately 135 men. The Battalion Commander was up the entire night making plans, issuing orders and visiting the aid station to do what he could to comfort the wounded. One wonders how the Battalion was able to make even a semblance of an attack on the following morning. 39

It is deemed desirable to bring out at this time that neither of the other two battalions of the regiment were committed on 16 November. Nor were either of these two battalions to be committed on the following day.